Is any war or battle glorious or is this myth propagated so that young men and women are willing to fight and die? I grew up on Marine Corp bases during the Vietnam conflict, the first war fought in full public view via our RCA and Philco consoles. When CBS anchor Walter Cronkite, who was called the most trusted man in America, traveled to Vietnam in 1968 and announced it was time for America to pull out, President Johnson reportedly told an aide, “If I’ve lost Cronkite, I’ve lost middle America.” I certainly felt lost. Maybe a battle that happened 100 years earlier would illuminate things.

Is any war or battle glorious or is this myth propagated so that young men and women are willing to fight and die? I grew up on Marine Corp bases during the Vietnam conflict, the first war fought in full public view via our RCA and Philco consoles. When CBS anchor Walter Cronkite, who was called the most trusted man in America, traveled to Vietnam in 1968 and announced it was time for America to pull out, President Johnson reportedly told an aide, “If I’ve lost Cronkite, I’ve lost middle America.” I certainly felt lost. Maybe a battle that happened 100 years earlier would illuminate things.

Visiting the battlefield at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania was on my bucket list and became a key motivator to make it to it this farthest point on my 2016 road ramble. Years ago, I was casting about for a book as my selection for that season’s book club list. NPR’s Nancy Pearl was talking with people around the country to find out what they were reading on summer vacation. A lifeguard from Rhode Island called in to recommend The Killer Angels, a work of historical fiction that looked at the Battle of Gettysburg from the perspective of commanders and troops on both sides. I had never heard of Michael Shaara’s Civil War novel

even through it had won the Pulitzer Prize in 1975. Turns out the book was mostly ignored until 20 years after publication and five years after Shaara’s death. In 1974, the country was so fatigued after the protracted mess of Vietnam that novels about war and warriors were out of favor. It took Ken Burns and his PBS series, The Civil War, which captured 40 million viewers, to resurrect the novel. Burns mentioned that The Killer Angels

had helped him develop an interest in the Civil War. Ted Turner saw Burn’s PBS documentary and funded the 1993 movie version of the book. Turner renamed the movie Gettysburg. Suddenly, The Killer Angels

was at the top of the New York Times Best-seller list.

The battle, with its bad and good decisions, missteps and faulty intelligence, acts of selfless courage and horrific death toll of both men and the horses who carried them or dragged their cannon – seems anything but glorious. Career military men were fighting men who had been their comrades a few short years before. Michael Shaara ruminated on how their dilemmas and divided loyalties added to the confusion of combat. Two thirds of southerners owned no slaves. Many northerners had never seen a black man. The grand purpose of this war was abstract to many of those waiting up on Cemetery Ridge and down low in the farm fields that surrounded it. Two huge armies filled with frightened, anxious men were waiting for orders to defend or attack. General Schwarzkopf described The Killer Angels as “the best and most realistic historical novel about war that I have ever read.” It has been required reading at different times in military academies and in officer training schools throughout the different service branches. My father probably read it when he was going through officer training after rising to the top of the enlisted ranks in the Marine Corp.

My friend Jackie and I left Maryland on a Monday morning in early June, headed up I-270 to US 15 North. Once off I-270, it was a quiet hour-long drive that gave us time to catch up after so many years apart. There are some people in your life you will always be close to, no matter how far and how long your separation. Jackie and her husband, Dewey and my husband, Hank and I married around the same time. We bought our first houses almost next door to each other, shared the victories and vicissitudes of our first career steps, and became parents around the same time. These life events bound us as well as a love of exploring new places and meeting new people. Jackie had already been to Gettysburg twice. I could not have a better road dog for my first time.

My friend Jackie and I left Maryland on a Monday morning in early June, headed up I-270 to US 15 North. Once off I-270, it was a quiet hour-long drive that gave us time to catch up after so many years apart. There are some people in your life you will always be close to, no matter how far and how long your separation. Jackie and her husband, Dewey and my husband, Hank and I married around the same time. We bought our first houses almost next door to each other, shared the victories and vicissitudes of our first career steps, and became parents around the same time. These life events bound us as well as a love of exploring new places and meeting new people. Jackie had already been to Gettysburg twice. I could not have a better road dog for my first time.

Even though over a million tourists visit Gettysburg every year, the area is remarkably tranquil and serene. Once we turned west onto PA 116, there were sporadic commercial developments but it had not become Disneyesque as I had feared. Entering town, there was a McDonalds and a few other fast food chains but we passed them quickly and entered Gettysburg proper. Many of the brick homes and buildings had brass plates by their doors signifying the structure existed in July of 1863. The old visitor’s center has been rebuilt and relocated farther south, away from its first location close to the national cemetery. According to Jackie, this center is much bigger to accommodate the ever- growing crowds which came after the twin boosts of Ken Burn’s documentary and the rediscovery of The Killer Angels

Even though over a million tourists visit Gettysburg every year, the area is remarkably tranquil and serene. Once we turned west onto PA 116, there were sporadic commercial developments but it had not become Disneyesque as I had feared. Entering town, there was a McDonalds and a few other fast food chains but we passed them quickly and entered Gettysburg proper. Many of the brick homes and buildings had brass plates by their doors signifying the structure existed in July of 1863. The old visitor’s center has been rebuilt and relocated farther south, away from its first location close to the national cemetery. According to Jackie, this center is much bigger to accommodate the ever- growing crowds which came after the twin boosts of Ken Burn’s documentary and the rediscovery of The Killer Angels. We got in line for tickets to the 20-minute film, “A New Birth of Freedom” which sets the stage for the battle. It was 10 am and the first film showing we could attend was at 11am. We also wanted to get a licensed battlefield guide for a personal tour of the battlegrounds. The earliest we could connect with one was at 2:30p. It was going to be a disjointed day but Jackie assured me it would work out well.

The film helped us appreciate the accidental nature of this monumental engagement and the horror when the unsuspecting Gettysburg community found itself suddenly in the middle. It was like going to bed after watching news reports of the Iraq war and waking up in Fallujah. While still mulling over why the battle happened at this place, at the film’s end, we were herded from the theater up two flights of stairs into a dark, circular tower. When our eyes adjusted, we were surrounded by the 1884 Pickett’s Charge cyclorama, a 360-degree oil on canvas painting 377 feet long by 42 feet high that depicts the noise, smoke, and carnage of the final Confederate assault. Our crowded group shared the vantage point of the Union defenders on Cemetery Ridge while explosions and flashes simulated Confederates coming closer and the forces converging, thrusting us into the front lines without the modern contrivance of CGI. We skipped the Gettysburg Museum of the Civil War, which contains thousands of Civil War relics, which along with the cyclorama inspired Shaara.

According to Phil Leigh in the New York Times Opinionator ,” One-hundred-and-one summers after the Battle of Gettysburg, a family of four stopped their Nash Rambler at the site during a 1,000-mile drive from the New York World’s Fair to Tallahassee, Fla. The father was a New Jersey-born former boxer, paratrooper and policeman who became a creative writing instructor at Florida State after enrolling to study opera. Before arriving at the park he had published dozens of science-fiction short stories, but nothing about history. But he had researched several Gettysburg participants for the trip… because Michael Shaara was in the early stages of creating his masterpiece novel, The Killer Angels.”

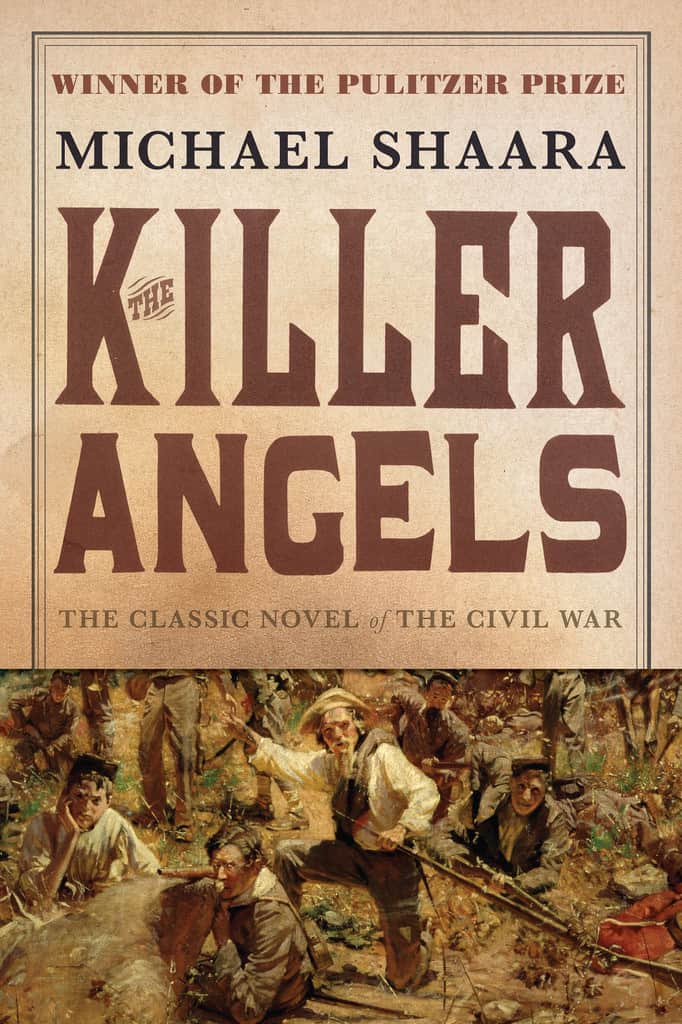

From another short film at the visitor’s center, I learned how contentious slavery was even before the creation of the Declaration of Independence. Many of the signers opposed slavery, which they felt had been super-imposed on the colonies by the British. Benjamin Franklin wrote that the Virginia Assembly had petitioned the King of England for permission to enact a law banning importation of more slaves into that colony. Renee Nal in “America’s Founding Fathers: How did They Really Feel About Slavery” , found that John Jay, the president of the Continental Congress spotlighted the hypocrisy when he wrote, “That men should pray and fight for their own freedom and yet keep others in slavery is certainly acting a very inconsistent, as well as unjust and perhaps impious, part.” George Washington, John Adams, John Quincy Adams, even slave-holding Thomas Jefferson all supported an end to one man owning another human. This controversy had been festering in America since inception. It was like a cat bite that heals over quickly only to continually erupt in a bigger and bigger sore until the infection was obliterated. The Civil War would begin the massive cauterizing cure.

It was 12:30 and we would not get our battlefield guide for two hours. Jackie and I decided to drive around the old part of Gettysburg. At the town center, the only parking space open was in front of the Wills house. The house is a National Park Service museum in downtown Gettysburg and tells the story of David Wills, Lincoln, and the Gettysburg Address which sounded like a boring, Lincoln-slept-here exhibit but it was air-conditioned and we had time to kill. It was anything but boring and in retrospect, completed the story of battle by telling its aftermath.

Ten roads lead into Gettysburg which had a population of about 2400 in 1860. Over four-hundred buildings housed manufacturing, shoemakers and tanneries plus retail establishments, surrounded by farmlands. Gettysburg’s roads and what lay along them drew 157,000 soldiers here to meet from July 1-3, 1863. One third of these soldiers would become casualties. Describing the town after the battle, HistoryNet.com recounts, “At field hospitals around Gettysburg, amputated limbs lay in heaps and were buried together. Bodies were collected at various points on the field and interred near where they fell…Homes, churches, any suitable building was pressed into service as a hospital…Apart from the human carnage, some 5,000 horses and mules died in the battle. They, too, had to be collected and burned in great pyres, leaving a stench that hung over the area for weeks.”

David Wills was an attorney living in Gettysburg. After the combatants left, Wills helped tend the wounded and lobbied for compensation for farmers and field owners who suffered property loses and asked the Governor for help to bury the dead. A permanent national cemetery for the Union dead at Gettysburg was suggested during a meeting at the Wills House. Wills invited President Abraham Lincoln to speak at the dedication of the cemetery and Lincoln stayed at the Wills home in November 1863. In his Gettysburg address, Lincoln took exception with the idea of a dedication. “In a larger sense, we cannot dedicate — we cannot consecrate — we cannot hallow — this ground,” the president said. “The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract.”

Just behind the Wills House and in front of a old store front now housing a thrift shop, we ran into a scarily realistic and life-sized Lincoln appearing to give directions to a tourist in a sweater and pink button-down shirt. On a 90 degree plus day, the layered outerwear of the tourist was as out of place as Lincoln amid tourists in athletic shoes and backpacks. The painted bronze is by J. Seward Johnson, Jr. and called “The Return Visit”. The Lincoln Fellowship of Pennsylvania placed it here in 1991. According to the fellowship,” it represents ‘the common man’ with Abraham Lincoln, showing that the Gettysburg Address is as relevant today as it was in 1863.” Reportedly, this bronze is the most true to life depiction of Lincoln and we spent some time examining his face from close up. On-line, many people likened the common man figure to Perry Como, who didn’t always seem that life like from my memories of his Christmas TV shows.

Eateries lined all four streets of Gettysburg Square, but Jackie is a meal packer. Years ago, she showed me around Washington D.C. and we ate on a blanket under the Carillon at Arlington National Cemetery while the Marine Corp Band played nearby at the Iwo Jima monument. For this tour, she had made paninis and brought the peaches we’d transported from the Blue Ridge Parkway. Driving back out to the surrounding battlefields, we found a shaded picnic table off West Confederate Avenue near Warfield Ridge. It was long past noon and we were alone among shading trees.

Back in my Subaru, we had a little over 30 minutes before we returned to the visitor’s center to pick up our guide. Many of the viewing spots were crowded with cars and buses spilling out passengers for the audio driving tour. The exception was Big Round Top Mountain. Privately owned in 1863, this mountain was too steep, wooded and rocky to have an artillery placement. Confederate snipers had possession until late the evening of July 2.

We took our pick of a dozen spots at the empty parking area and found where fighting had followed a stone wall up the slope. Avoiding tangled roots and poison ivy, I climbed to near the summit and found a simple rectangular marker on a rocky outcropping. The engraving on the downhill side read ,” The 20th Maine Reg. 3d Brig. 1st. Div. 5th Corps Colonel Joshua L. Chamberlain captured and held this position on the evening of July 2d, 1863, pursuing the enemy from its front on the line marked by its monument below. The Regt. lost in the battle 130 killed and wounded out of 358 engaged. This monument marks the extreme left of the Union line during the battle of the 3d day”

Joshua Chamberlain was wounded six times, earned the Medal of Honor, and went on after the war to serve as Governor of Maine and President of Bowdoin College. He captured the imagination of Michael Shaara and became one of the best known participants in the Battle of Gettysburg due to The Killer Angels and the movie it inspired. Big Round Top also had monuments to the 5th, 9th, 10th, and 12th Pennsylvania Reserves along with the 118th and 119th Pennsylvania Volunteers and the 9th Massachusetts Volunteers. In all, there are over 1300 monuments in Gettysburg to regiments, batteries, and individuals. Jackie told me new monuments are no longer allowed to be erected at the battlefield. The markers are so plentiful and diverse along some roads that it can seem like the Roman emperor Hadrian’s villa. The memorials on Big Round Top were widely spaced, weathered, and simple. They blended into the boulders and trees and were somewhat hidden from each other as the different patrols would have been during the night of July 2.

We drove back to the visitor’s center to pick up our Licensed Battlefield Guide. We had signed up for the final tour slots of the day, which would last until 4:30 or 5P. Jackie and I sat on benches across the lobby from the will call window. One by one, men and women with clipboards and matching hats started coming out of a door to the far left of the admissions area. They would first go the will call window and then cross the lobby towards us, calling out names to find their charges. An incongruous thought struck me. The guides paraded out in single file like beauty pageant contestants who affixed an on-stage smile as they came forward to met each group. Our guide, Andy would have been Miss Vermont. He was middle-aged, owned and worked at an electronics store in Stowe during the ski season. He was single and had a BA in History, which he was happy to use every summer as a Gettysburg Guide. He had been coming south for the summer for at least a decade, living in a one- room efficiency and working with a couple of groups each day. As he asked for my keys, he said one perk of being a guide was getting to test drive lots of different makes and models of cars. He adjusted the Subaru’s driver seat back to its farthest position, and we set to see where North first met South.

We drove through the town of Gettysburg and out to the northwest where on June 30, 1863, scouts from John Buford’s Union cavalry first entered Gettysburg and realized Confederates were close. We idled in a parking lot for a restroom used by the tour buses. From there, we had a clear view of the open and gently sloping land where the first shots would be fired. Andy painted the picture as Buford took cover and hurriedly sent a message to Major General John Reynolds in Maryland to bring his infantry. The two massive armies have been seeking each other for weeks and Buford’s cavalry stood between them.

As we drove to the site of the first day’s battle, Andy helped us decipher some of the hundreds of markets. He explained that Union bridgade HQ’s had square bases, Confederates had round. Division and corps headquarters are rectangular with rectangular bronze plaques and so forth. “Will there be a test?” I wondered.

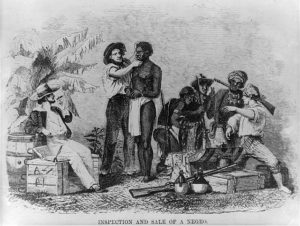

Parking by a line of trees near McPherson Ridge, Andy pointed out where Reynolds and his troops arrived around 10:30a on July 1 to reinforce Buford, who has been fighting since 7:30 that morning. Reynolds, according to Andy one of the most romantic figures of the conflict, was killed almost immediately while placing his troops. After the battle, Reynolds body was collected and found to be missing his West Point Ring. For a man who was married to the military, it was unthinkable that he had lost it. Andy told us that the mystery was solved when a woman named Katherine May Hewitt revealed that she had it. She and Reynolds were engaged but kept is a secret because she was Catholic and he was Protestant. Together they agreed that if he died in the war, she would enter a convent. After his burial, Katherine traveled to Emmitsburg, Maryland, and joined the Order of the Daughters of Charity. You could tell how touched Andy and many men would be by the undying love on both sides. We pragmatic women, perhaps more hardwired for the preservation of the species, might decide that Katherine and General John wasted the time they would have had together.

Because we had Andy driving just Jackie and me, we could stop at will and he could point out nuances and mistakes that eventually changed the battle outcome. Throughout the day on July 1, divisions from both sides of the conflict were arriving. At 2:15p, Robert E. Lee got there. We drove to the Eternal Flame monument where at 3p (around the same time of day that we are there), the Confederates attack with their biggest division. At 4p, Jubal Early (my favorite southern name) arrives with his division, attacks, and crushes the Union’s “Dutch Corp” which causes the Union line to start collapsing. The Union retreats to Cemetery Hill and at 5pm, it looks like Lee has won another stunning victory. At midnight, Union General Meade arrives and decides to make a stand on Cemetery Hill.

By 4pm on July 2, the entire Army of Northern Virginia was at Gettysburg. Skirmishes blew up from late afternoon until dusk and overnight there was frequent firing by pickets and the Big Round Top kerfuffle.

Andy drove us past Confederate-held positions like the Rose farm, the Peach Orchard, the Wheatfield, Trostle farm, and Devil’s Den. Andy was not a fan of Union Major General Daniel E. Sickles, who sounded like a posturing politico as inept as Joshua Chamberlain was competent. However, Sickles was not without inventiveness. At Devil’s Den, he had a leg shot off and preserved it in formaldehyde.

On July 3 at 4:30a, the Union commenced the battle for Culp’s hill. Attacks and counter attacks went for seven hours. At 1pm, Jeb Stuart’s Confederate cavalry went after General George Custer on the Union’s rear on Cemetery Ridge.

Around that same time, two cannon shots signal that it was time to concentrate the Confederate attack on the copse of trees on Cemetery Ridge. Andy had shown us the vantage point where Lee had contemplated this final attack. While it looked like a straight shot across the fields, from the Union position looking back, it was more apparent how undulating the terrain is and how much ground the Confederates would have to cover. Between 2 and 3p, General Longstreet gave the order for Pickett’s charge and at 4p, about 200 Confederate troops madeit to the stone wall but are repelled. The tide of the battle and ultimately the war had turned.

With Andy, we stared inside cannon, walked in the steps of foot soldiers on both sides and climbed up and onto the defensive positions on Little Round Top and Cemetery Ridge that we had experienced with the 1884 Cyclorama five hours earlier. As quickly as the battle had materialized, the forces moved on, leaving behind destroyed fields and homes, wounded, dying and dead men and livestock that would take Gettysburg and David Wills years to clean up. Lincoln would join the dead less than two years after his Gettysburg address.

Is any war or battle glorious? For me, the answer is no. However, sometimes it is necessary.

Road Ramble 2016 – The Blue Ridge Parkway and Skyline Drive area

Road Ramble 2016 – Asheville, North Carolina

Road Ramble 2016 – Mississippi and Alabama at Lookout Mountain

Road Ramble 2016 – New Orleans and driving through Louisiana