POST MAY CONTAIN AFFILIATE LINKS- READ DISCLOSURE FOR INFO.

Go To Big Bend National Park Now!

Go To Big Bend National Park Now!

If you’re a Texan raised on our Gulf Coast or in East Texas, and you have not visited Big Bend National Park, promise me that when you finish this blog, you’ll pick a date and go. It is that important to your Texas psyche. If you are a transplanted Texan like me, it is still a soul awakening experience, but at least I’m not at risk at having a Native Texan bumper sticker torn off my Subaru.

But first, you have a decision. To find five compelling reasons to visit Big Bend National Park as soon as click here. Or I’ll tell you about most of them in this post along with interesting, and for me, frightening adventure my son and I had at Big Bend. Lastly, you can get right to the adventure by clicking here. I give you these choices because I always love to read an unbroken and detailed narrative! So I’ve left it up to you.

The least visited national park

Big Bend is hauntingly beautiful or beautifully frightening depending on how enamored you are with having neighbors and conveniences nearby. It is one of the largest, most remote, and least-visited national parks in the lower 48 United States which makes it great for that fact alone. Five paved roads thread through Big Bend.

The Rio Grande river is the 118-mile southern border of the park. Canoers and rafters love it because it flows through spectacular canyons of Santa Elena, Mariscal, and Boquillas. Outside the southern boundary lies Mexico and Parque Nacional Cañon de Santa Elena.

The darkest skies in the US

In 2012, International Dark-Sky Association recognized Big Bend as having the darkest measured skies in the lower 48 United States. The night sky is so star-filled, for city-dwellers like us it is hard to believe you are not in a planetarium show.

Obligatory Cabeza de Vaca connection

Cabeza de Vaca stumbled close to Big Bend around 1535. With his horrendous sense of direction and general bad luck which led to shipwrecks and enslavement by native tribes, de Vaca discovered and wrote about huge areas of Texas, and Mexico. I have yet to visit somewhere in Texas that Cabeza de Vaca didn’t at least drive by. Cabeza de Vaca and his companions were the first Europeans to see this area. Artifacts show various nomadic tribes had been living there, at least seasonally, for thousands of years.

Indians, Spaniards and Buffalo Soldiers

At the beginning of the 18th century, Mescalero Apaches and later Comanche invaded the area. The Spanish piled on with a line of forts or presidios to protect what was then the northern frontier of New Spain. Spain was unsuccessful at taming either the Indians or the land, and the presidios were abandoned. After the end of the Mexican–American War in 1848, in came US Army forts manned by “Buffalo Soldiers, the name given to African-American troops by Native Americans. They fared somewhat better.

Drive to preserve Big Bend as a park

A mining boom in from the late 1800s into the 1930s brought in more people trying to make a living in the area, but the boom had played out by 1940. This brief flurry of domestication worried those folks who had come to love Big Bend for what it had and didn’t have – the geography of wide contrast and beauty with little alteration by humans in spite of so many attempts. In 1933, Texas Canyons State Park was established and then changed to Big Bend State Park later that same year. In 1935, federal legislation was passed to buy the land for a national park and start building. On July 1, 1944, Big Bend National Park opened to visitors, thanks in part to one final invasion.

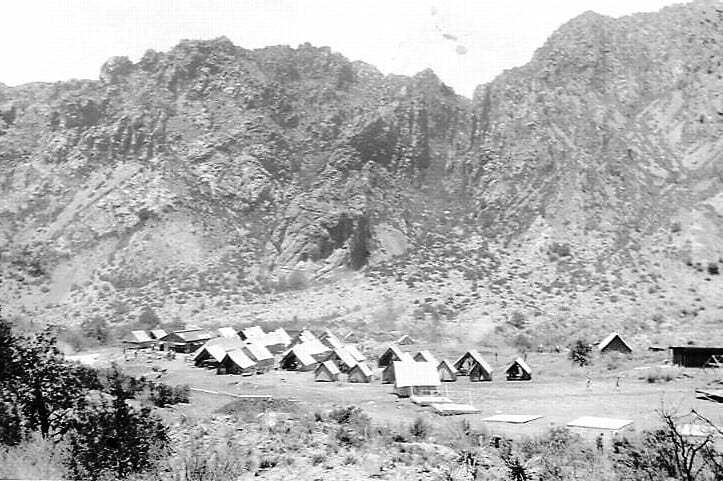

Roosevelt’s Tree Army

Two hundred members of Roosevelt’s tree army, as the Civilian Conservation Corps was nicknamed, arrived in 1936 to set up camp and develop a reliable water supply, the first steps to creating Big Bend National Park. Initially, unmarried men between the ages of 18 and 25 and from families in need made up the CCC. Enlistment was for six months with the option to reenlist up to two years. Pay was $30/mo with all but $5 sent home to the family. Eight out of every ten men working with the CCC in Big Bend were Hispanic. Many had never been away from home, and now they were living in tents (later barracks) 85 miles from the nearest towns.

Big Bend’s CCC Legacy

According to the National Parks Service site – “If you have driven, hiked, or slept in the Chisos Mountains, you have experienced CCC history… The CCC built an all-weather access road into the Chisos Mountains Basin. They surveyed and built the seven-mile road using only picks, shovels, rakes, and a dump truck, which they loaded by hand.”

“They scraped, dug, and blasted 10,000 truckloads of earth and rock and constructed 17 stone culverts, still in use today along the Basin road…The CCC built the Lost Mine Trail, a store, and four stone and adobe cottages still used as lodging today. These CCC boys surveyed the park boundary and established trail and facility locations.”

The last CCC camp closed in 1942 as World War II loomed. It is hard not to be moved by what they left behind for us in Big Bend.

Sharing Big Bend with my adult son

We first took our kids to Big Bend when they were in elementary school. Now 29, my son Shane would have been too old for Roosevelt’s “Tree Army.” Growing up in Houston as a Boy Scout, he’d camped, paddled and hiked all over Texas and into New Mexico and North Carolina. Now he is a surveyor.

His job and scouting past make him appreciative of the work and vision that went into preserving this 800,000-acre gem. When we pulled up at the park entrance and paid our $25 entrance fee, I heard Shane whisper to himself, “Why did it take me so long to get back to this?”

Find out where to hike

The November weather was unusual that first day – dreary, rainy and intermittently cold. We drove on to park headquarters at Panther Junction so Shane and I could look at a 3D model of the hiking trails and canyons.

We had missed this step on our first visit many years ago and hiked off without an idea of the elevations we would be encountering. I have an almost paralyzing fear of heights as you may have read in my adventure with the Port Isabel lighthouse. On that first hike in Big Bend many years ago, the trail ran out at the top of Santa Elena Canyon. I suddenly realized I was high up on a relatively narrow gorge. The sheer cliff walls tower as much as 1/4 mile above the river on both sides.

This time, Shane used the 3D model to point the Pinnacle trail that ran 3.5 miles to connect with the Emory Peak trail to the top. Pinnacle was a forested trail, and he thought we could do it together to get our hiking legs back under us. We backtracked three miles to the turnoff for Chisos Basin and drove up a six-mile curving mountain road to the Chisos Mountain Lodge and Visitors Center where Pinnacle started.

Heading up Pinnacle Trail

We loaded up on water, trail mix, and maps at the store and headed out. Shane hadn’t worn his hiking shoes in the twelve years since Philmont Boy Scout Camp in New Mexico. Still, they appeared to be holding up fine. I no longer had hiking shoes and walked in some bright blue New Balance shoes and paddling/hiking clothes from my boundary waters trip.

Sub-adult bear sighting

At first, Shane’s worry was possible thunderstorms while we were hiking. Mine was sudden drop-offs that might make me panic. Both of concerns were soon replaced.

We’d only walked a little way up the trail when we met a lone hiker – an older woman in a windbreaker with a large set of binoculars hanging from her neck. Music was blaring from her smart phone.

“A sub-adult bear just crossed my path less than a mile up the trail,” she warned us. “Make as much noise as you can while you are on the trail,” she advised. “I met two girls on the trail who had also crossed paths with a smallish bear, so he’s found something good to eat up there,” she continued.

We asked the woman to clarify “sub-adult bear.” “He’s older than a cub, maybe just newly on his own,” she said knowledgeably. Great, we were newbies who did not know hiker protocol sharing the trail with an equally clueless bear. “Do I smell trail mix?” Shane mimicked in a “BooBoo the Bear” cartoon voice.

Bear shooing with Cat Stevens

Shane and I don’t talk much when we walk or hike. The ground was slightly damp, so our steps didn’t make much noise. I chose a random song on my iPhone and “Longer Boats” blared out by the singer formerly named Cat Stevens.

“Who is that? I like it, “ Shane asked. “One of my favorites when I was younger. Beautiful lyrics with very deep, caring, spiritual messages,” I told him. “He later changed his name to something Islamic sounding and got on the ‘no-fly’ list.”

As far as we know, bears are above politics. I found the entire “Tea for the Tillerman” album and played it on our way up to the bench lookout about a mile or so up the trail.

Because of the rainy weather, we met a few other hikers, and the bear sighting was bothering me. We also heard some distant rumbles of thunder. Shane knew I was concerned and suggested we hike down to the Chisos mountain loop and a part of the window trail. We had gotten a late start, around 2p and it was now close to 4.

Scouting for Boquillas

“I want to come back earlier tomorrow and climb to the top of Emory,” Shane said. It was his birthday trip, and I could tell he was enjoying being out in the wilderness. He would do that hike without me slowing him down, but it would still take some time to make the 10.5-mile round trip.

Before we headed back to Terlingua, we drove down a park road to the Boquillas crossing, a small but heavily secured border checkpoint. It was impossible to see the Rio Grande beyond the fences and stone building.

Wanting to see Mexico from some park vantage point, we continued down a side road to the Boquillas Canyon Overlook. That was a happy decision. We had gained an unvarnished view into how, in years past, Mexico had been a big part of the Big Bend experience.

Down below us and across the river, some men were milling under a copse of trees. A couple of horses were saddled and waiting. A small goat wandered around the riverbank. I choose to believe the goat was a pet and not pre-BBQ.

Boquillas comes to us – our souvenir

Beyond the men, you could see the brightly painted buildings on Boquillas up on a plateau. The late afternoon sun was muting the colors into softer pastels.

There was a big flat stone by the edge of the canyon overlook, and someone had placed a plastic bucket in front of the rock. On the top of the stone were all kinds of wire sculptures with price tags on them.

The hand-lettered sign on the bucket said “Honor payment. Hand made by residents of Boquillas.” We took a copper wire scorpion with purple beads for eyes and left a $10 bill. One of the men must come across to get the bill after we’d left the overlook.

Boquillas before 9/11

As hard as 9/11 attacks had rocked the US, it had almost wiped Boquillas off the map. Boquillas was a small town of around 300 residents, primarily dependent on the Big Bend tourist trade. Visitors would cross the Rio Grande to visit the village’s bar, restaurant, and taco stands.

Tourism options included pony and donkey rentals, parties at Park Bar, and overnight stays at a local breakfast known as the Buzzard’s Roost. Texas music star Robert Earl Keen’s song “Gringo Honeymoon” was said to be about a day he and a female companion visited the village.

Boquillas after 9/11 and now

With the closing of the international border crossing as after 9/11, the town’s economy was destroyed, and most people moved away. The crossing reopened in 2013.

Now with limited hours of operation, Boquillas has prospered enough to get electricity brought over from the US side and a single telephone line which now serves the village.

Boquilla’s sense of humor is appealing. I found a somewhat self-deprecating statement told about the village by persons who live there. “Boquillas del Carmen has 200 people, 400 dogs, and one million scorpions.” Let’s hope the copper alacrán now riding on our dashboard was not pregnant.

A second go at Emory Peak

We got back to Terlingua close to sunset, took turns taking our first shower in Alice’s tiny bathroom and made plans to pack up and return to Big Bend the next morning. Returning to Chisos mountain by 11 the next morning, I walked up with Shane to the same spot we’d made it to the day before. We drank some wáter. Shane hooked up with some other climbers going to the top of Emory Peak. I headed back down to wait for him in the basin.

I toured the Chisos Mountain Lodge, hiked on some smaller, more populated trails and pulled out the book I’d bought in Alpine by Jim Glendenning. Glendenning was a Scot who had made his home in West Texas for many years. I went back to the visitors center to learn more about the animals lived in the Chisos Mountains. While there, I overheard one ranger tell some hikers they were seeing record bear activity during the last few days.

Record Bear Activity

Someone in line for information said he had seen a bear by the side on the road on the drive up the mountain. Lost Mine Trail was closed because a mama bear with cubs had been spotted a couple of times the day before.

“The Rain last week has brought out the berries and nuts,” said one of the rangers, “The bears are going crazy filling up.” I was glad I wasn’t on the trail, but I worried about my 6’2’ baby boy. (Checking the NPS site after we got home, there were 108 bear sightings in November 2016, over two to three times what is way in the months before.)

Sly Foxes

To distract myself, I read about the javelinas, mountain lions, and foxes. The pictures of the foxes were unbearably cute, and the text below answered a question I’d had when we hiked yesterday.

You weren’t supposed to take dogs on the hikes, but every so often, it looked like a poodle had pooped in the middle of the trail. Not Chihuahua piles or a pit bull dump either. It turns out the culprits were the foxes. “Hardly ever seen but always around, the fox is likely to leave scat on the trail,” read the info board or something to that effect.

Shane makes it to the top

Shane made it down around 3:30p. He was ecstatic and exhausted. I was thrilled he had summited but worried about the late start we were getting out of the park. We’d lost an hour of daylight because of the time change that day.

We were spending the night in Marfa, over two hours away. Between us lay the treacherous River Road and the Big Hill, a route I didn’t want to do in darkness. Little did I realize, we’d have a scare on the River Road way before the sunset. But that adrenaline rush was still a few hours away.

Thanks for reading. I love exploring.

David, I was so touched by your comment. I completely believe that losing my position was a God-given gift. I’m wishing that you and all my friends start living their dreams, if only in a small way. Time is not a guarantee but life is what we make it, wherever we find ourselves. Love to you and your family.

Linda