After the three-day layover in Asheville, Mary Ann came along for the seven to nine hour drive to Maryland to see some more invasive Texans who now called Maryland home. Because our friends were teachers and had graduation ceremonies on Friday, we waited until noon on Friday to leave Asheville. That would break up the trip and get us to Gaithersburg on Saturday afternoon. We also got the opportunity to scare some poor guy in a Motel 6 outside Roanoke when M.A. and I misread our key card and tried to break into his hotel room. Fun and games on the road.

We wanted to travel at least part of the way along the Blue Ridge Parkway. Combined with the Skyline Drive in Virginia, these ridge roads would take us over 490 miles in the right direction but still left us 80 miles shy of our final destination. Figuring on top speeds of 45 mph and frequent 25 mph sections, using the BRP for the entire trip could take all weekend. We’d jump on and off, using I-81 to make up some time. Our plan was to pick up the Blue Ridge Parkway north of Asheville to avoid the Biltmore congestion. That decision looked good on paper.

We left Asheville on I-40 and picked up US-70 at Old Fort. At Pleasant Gardens, we turned onto Highway 80 and started to spiral up for the next several miles. It was like driving inside a forested silo as far as the line of sight went. We had exchanged the congestion in Asheville for a path of no return – no turn-arounds or shoulders and very few cars coming the other direction. Mary Ann swallowed a Dramamine. My fingers were starting to cramp from tightly gripping the steering wheel. There was a reason AAA had not taken us this way on our Triptik.

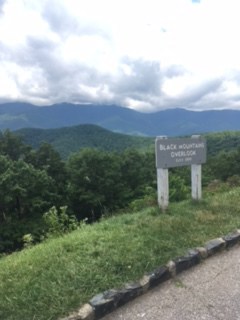

Coming out of another seemingly endless blind curve, we came to an intersection. A pullover beckoned like a Ulysses siren from across the road. Mary Ann and I swerved in, getting withering looks from two outdoor types in an SUV enjoying their moment with nature. Mary Ann jumped out of the car and gulped in fresh air. I shook and wiggled my fingers and did some moving in place exercises to get blood flowing after a permanent clinch of all voluntary muscles for the last thirty minutes. Our “Texas” license plate confirmed for our neighboring SUV-ers that the flat-landers had arrived. Finally, we saw the sign. We had made it onto The Blue Ridge Parkway.

Originally called the Appalachian National Scenic Highway, the BRP was started in 1935 under Franklin D. Roosevelt using mostly private contractors. Various New Deal public works agencies did some of the work, including the Works Progress Administration (WPA) for some roadway construction, the Emergency Relief Administration for landscaping and developing recreation areas and the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) for roadside cleanup and plantings, grading slopes, and doing some improvement on adjacent fields and forest lands. During World War II, conscientious objectors in the Civilian Public Service took over from CCC and the young men who were fighting in Europe and the Pacific.

According an article called “Designing the Parkway” in the Blue Ridge Parkway Directory and Travel Planner, “Overall, the Parkway was to reveal the charm and interest of the native American countryside as the designers perceived that to be. Log cabins, and barns, rail fences and pioneer ways were looked upon much more favorably than some of the more modern presentations of America that had already found their way into the mountains in the 1930s and 40’s.” The Parkway’s construction created needed jobs but there were losers in the project too – displaced residents and landowners and farmers who faced new regulations, including how crops could be transported. Land use and development was limited to agriculture and no commercial traffic could use the Parkway so equipment, materials and produce had to travel on side roads.

Once again, the Cherokee were affected. This time, it was the eastern band of Cherokee. The Parkway was to be built through their lands. Perhaps learning from past dealings with the US government, the Cherokee refused to give up right of way until 1940 when they negotiated payment for their land. They also demanded and got the state to build a regular highway through the Soco Valley. It is now part of US 19.

Most of the Parkway project was completed in 1966 except for a portion of the area we were traveling. This stretch included the Linn Cove Viaduct and Grandfather Mountain and didn’t open until 1987, fifty-two years after the start of construction.

We’d entered the Blue Ridge Parkway at Buck Creek Gap at Mile 344. Every mile or three was an overlook – Black Mountain, Three Knobs, Deer Lick Gap. Those were three to stop at before we’d even gotten as far as Little Switzerland off to the east at Mile 334. Little Switzerland was built in 1910, a very old world mountain lodge with cottages, restaurants, tennis and golf. It presented a jarring contrast between the displaced mountain folk and the people who could vacation at Little Switzerland in the early part of the century. But we were here for nature not comfort so we drove past the resort and headed for Linville Falls.

The Linville River starts on the steep slopes of Grandfather Mountain and descends almost 2000 feet through a rugged gorge, prompting the Cherokee to call the river “Eeseeoh” or “river of cliffs.” To get industrialist John D. Rockefeller to pick up the tab for the Linville Falls property, he was treated to an al fresco lunch to take in the grandeur. The picnic was spread out in view of the falls and coincidentally close enough to hear the noise from sawmills diligently deforesting the slopes like a bevy of beavers. The picnic plan worked perfectly. As we snacked and visited with picnickers along the shaded river at the Linville Falls visitor’s center, we raised a Yeti rambler to ole’ John D and his gracious gift.

Our dilemma how frequently to stop at a visitor center or overlook on the Blue Ridge Parkway. Each stop gave you a chance to pause and savor the scenery but a drive provided an unfolding view of both the majestic surroundings and the virtuoso design the planners and builders of the Parkway had achieved. The Parkway was meant to “lie gentle on the land” and this intention was well met. Bridges merged into the roadways with continuous shoulders of grass. There was no side stripping on the road to create a hard line between the pavement and natural setting. Many times, the long and distant views opened up to delight just as you come out of a curve. Because there are few straight lines in nature, on the Parkway, one curve flowed into the next like a river. Fences are made of stone, wood or different combinations to blend into the fields and forests. “Look!” was an overused word that afternoon in our car. How could you take it all in? I now see why the Parkway is a destination to visit often, slowly moving your camping base a few miles down the road every year to explore it piece by lovely piece.

“The result: the Linn Cove Viaduct at milepost 304.6, the most complicated concrete bridge ever built, snaking around boulder-strewn Linn Cove in a sweeping “S” curve”. Construction began in 1979 and the challenges faced and overcome where massive. For a complete history of building this “missing link” on the Parkway, read more at The National Park Service Once again, the Parkway builders had created a compelling compromise to preserve a scenic treasure.

Moses, a textile entrepreneur, founded a company that became a major supplier of denim to the Levi Strauss and Company. Using the profits from the excellent timing of his venture, Moses and Bertha Cone began acquiring land in the 1890s in the Blowing Rock area for his house. Reporters of the time nicknamed him and his blue blood counterpart “Farmer Cone” and “Farmer Vanderbilt”. The total estate had a twenty-three room mansion (now re- purposed as an art center), twenty-five miles of carriage lanes, livestock, gardens, and an extensive orchard plus a number of other buildings including a bowling alley (since torn down). The manor house is at an elevation of 4500 feet and looks down on an azure lake. Its location is ringed by mountains including the one that gave the house its name – Flat Top Mountain. Because of its location and the working nature of Moses Cone’s estate, it was easier to believe that a family had happily lived and prospered here. On my visit to the Biltmore, living day to day in that elaborately furnished mausoleum seemed inconceivable.

We left the BRP right after the Cone Manor and headed west to Boone, NC. Boone was named after Daniel, the frontiersman and 60’s TV show character. The town was settled by some of his nephews. It is the home to Appalachian State University and it may have been graduation at the college because all the sidewalks downtown and around the school were swarming with what looked like proud parental units. Railroad enthusiasts visit Boone to see the narrow gauge East Tennessee and Western North Carolina Railroad (nicknamed “Tweetsie”) which operated until the flood of 1940. Mary Ann was interested in Boone because it apparently had a reputation akin to Roswell New Mexico for UFO’s and alien abductions. The epicenter of all the interest is Brown Mountain and its mysterious lights. According to BrownMountainabductions.com, people have been disappearing after seeing the lights for centuries, including twenty-seven people vacationing at a popular campground in October 2011. How did I not read about that? The only thing getting abducted during our visit was a bag of peaches from a truck farmer in the parking lot of a hardware store. We spirited them away to a Motel 6 in Roanoke for vivisecting.

On Saturday morning we headed up Interstate 81 until we tired of the fast pace. Leaving the freeway near New Market, we drove east on US 211 , winding along and over the Massanutten Mountain and across the South Fork Shenandoah River. The road enters the Blue Ridge Mountains in the Shenandoah National Park. At Thornton Gap, we connected for a short time with Skyline Drive. Skyline Drive takes up where the Blue Ridge Parkway runs out. It travels 109 miles along the Shenandoah National Park and is another legacy of the Works Progress Administration (viva WPA!), begun in 1930 and finished in 1939.

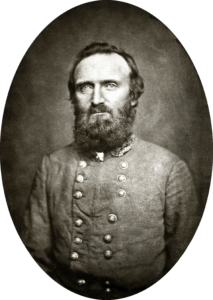

We didn’t realize until we read the Shenandoah National Park website that we were “driving along one of the most significant tools the Confederacy utilized during the American Civil War.” According to the website, “Throughout the four years of the Civil War (1861-1865), Confederate armies frequently used the Blue Ridge Mountains as a natural screen to conceal the movement of troops from Union forces. Because of the southwest-northeast orientation of the Shenandoah Valley west of the Blue Ridge, Confederate armies marching down the Valley naturally moved toward a position from whence they could threaten the northern cities of Washington and Baltimore, while Union armies marching up the Valley were forced to move farther away from the Confederate capitol of Richmond.”

The confederate commander who made best use of the Blue Ridge in this area was the fervently religious General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson. Using cover from the ridge and his knowledge of its gaps and valleys, he and his 17,000 men won five significant victories in the Valley campaign against a combined force of 60,000. Like most of us, Stonewall was a flawed but heroic ball of wax. He was an instructor at the Virginia Military Institute and parts of his curriculum are considered timeless military strategy and still taught, yet Jackson was an unpopular teacher. Peculiar in his personal habits, humorless and a hypochondriac, Jackson was at the same time revered by both free black men and slaves around his hometown of Lexington, Virginia. According to historian James Robertson, “Jackson neither apologized for nor spoke in favor of the practice of slavery. He probably opposed the institution. Yet in his mind the Creator had sanctioned slavery, and man had no moral right to challenge its existence. The good Christian slaveholder was one who treated his servants fairly and humanely at all times.” In the spring of 1862 his daring success in the Valley campaign made Jackson the most celebrated warrior in the Confederacy. In May 1863, he was shot by Confederate pickets at the Battle of Chancellorsville, had his arm amputated and died eight days later. His last words were, “Let us cross over the river, and rest under the shade of the trees.” We were taking Stonewall’s heartfelt advice.